How to build a regression NLP model to improve the transparency of climate finance

If you read the description of a World Bank project, would you be able to guess how much of it was spent on climate adaptation? BERT might be able to.

If you want to skip my explanation of how this model was built and just get stuck into the code, it’s all available in this Apache 2.0 licensed repo: https://github.com/akmiller01/world-bank-climate-regression

Or if you want to just skip to the results and implications, click here.

Background

Using a language model like Google’s BERT in order to classify text is nothing new. BERT is fundamentally trained in the masked language modeling task, meaning that a certain percentage of tokens within a text are hidden and the model is trained to fill them in. But the authors of BERT had classification in mind as one of the possible downstream tasks for the model. The BERT tokenizer includes a special class token ([CLS]) at the beginning of each text and the model includes a pooler layer which returns the embedding vector for the whole text.

Even with relatively messy real-world text data, BERT excels at binary classification. Starting with a multilingual implementation of BERT (bert-base-multi-lingual-uncased) and fine-tuning it on the masked language modeling task for development and humanitarian text for 3 epochs (yielding ODABert), I was able to achieve a 91% accuracy rate in classifying development project text with only 7 additional epochs of training into two classes: no relation to climate finance or climate adaptation/mitigation as a principal objective (model weights available here).

Models like these have formed the backbone of my climate finance analysis to date. Although some donors do a good job of correctly labeling their climate adaptation and mitigation projects, these models help fill the gaps for those that don’t.

The issue with labeling aid

Whether aid is labeled directly by the donor reporting it or by an NLP model like the above, the nuance of exactly how much is spent on climate finance is lost by classifying the entire project. Taking the World Bank for example, should all of the money disbursed as a part of an “Oil Rehabilitation Project” that primarily focused on drilling new oil wells and laying pipelines count as climate mitigation finance because a component of the project included “natural gas liquids extraction units to recover hydrocarbon liquids and reduce flaring, thereby reducing CO2 and particulate emissions”? Obviously not. Thankfully, the World Bank themselves have done a reasonably good job of breaking out the exact percentage of each project that should count. They state that only $112.6 of the total $866 million (13%) for the Oil Rehabilitation Project above should be counted as climate mitigation.

The World Bank is exceptional in this level of climate finance metadata. Almost 1/3rd of all projects in the OECD DAC CRS since 2017 (610,615 out of 1,925,079) have not even been screened for climate adaptation or climate mitigation project objectives, let alone broken down into exact percentages.

Building an NLP regression model

If we can build an NLP model that is able to correlate how World Bank projects are described in their project text with the exact percentage of the project that went to climate adaptation and mitigation objectives, we might be able to learn more about World Bank climate projects, improve the accuracy of climate finance reporting for the Bank, and ultimately extrapolate the results of the model to other donors.

This new model starts with data collection. While the World Bank reports all of their projects to the OECD for inclusion in the CRS, the CRS does not have the ability to report climate adaptation or mitigation by exact percentage. The World Bank’s reporting to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) does include their climate finance percentage splits through the sector vocabulary 98, but the text descriptions can be a little terse. Through the World Bank’s project API V3, we can access not only the exact percentage splits, but also project abstracts and full project development objectives. Documentation on how to access and use the API is available here.

Next, we can use Huggingface’s transformer library to not only easily access my pretrained weights for ODABert, but also train a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layer on top of it. If you take a look under the hood at how their BertForSequenceClassification class is defined, the forward function will use the correct loss function for a regression (MSELoss) if the number of labels is equal to 1 or the “problem_type” model argument is set to “regression.” We can take our data from above, transform the climate finance percentages into a 3-dimensional label vector, and set the problem type accordingly:

def preprocess_function(example):

labels = [example['Climate change'], example['Climate adaptation'], example['Climate mitigation']]

example = tokenizer(example['text'], truncation=True)

example['labels'] = labels

return example

dataset = dataset.map(preprocess_function, remove_columns=['text', 'Climate change', 'Climate adaptation', 'Climate mitigation'])

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained(

'alex-miller/ODABert',

num_labels=3,

problem_type='regression'

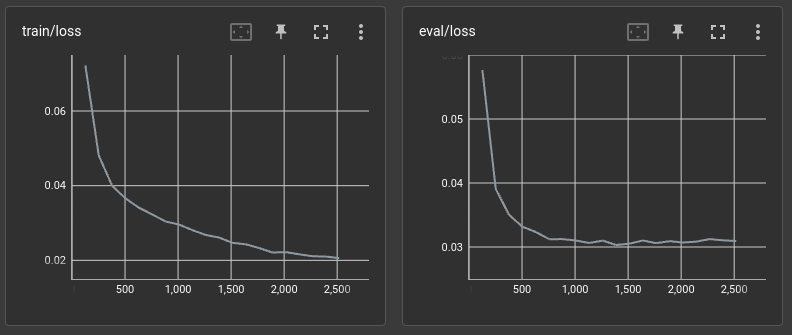

) The pooled layer embeddings from ODABert, representing the contextual meaning of the text, are then fed into the classifier MLP layer for training. Through 20 epochs of training, the mean-squared error drops from 0.07 to 0.02 for the training data and 0.06 to 0.03 for the reserved testing set. Better results are likely possible through hyperparameter tuning, as the testing loss largely stalled after the first 11 epochs. Full model weights are available here.

Results

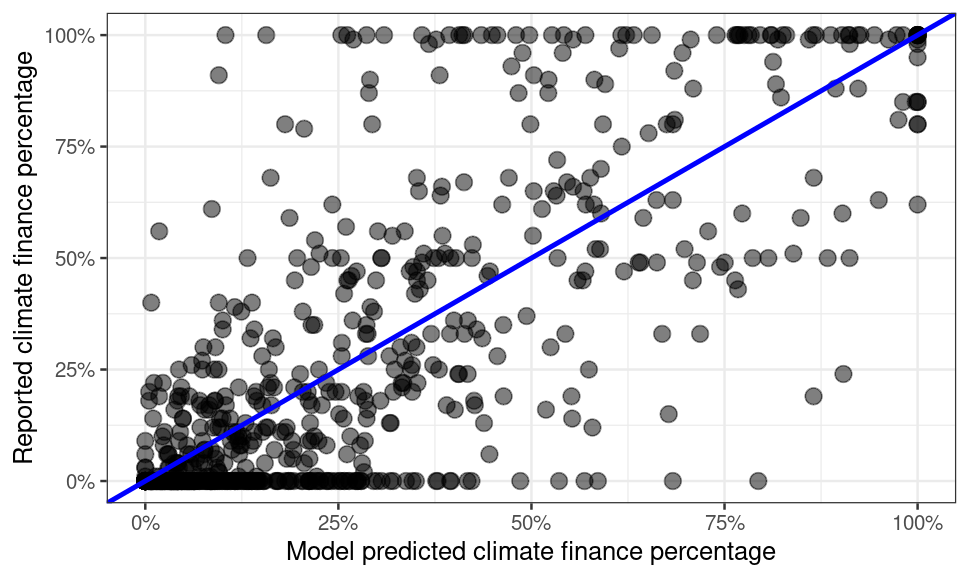

For a model that only has access to information that BERT is able to glean from the textual descriptions of World Bank projects, the accuracy is impressive. From the 754 projects in the reserved testing set, the model is able to correctly guess to within 20% of the labeled overall climate finance percentage for 576 (76.4%), within 20% of the climate mitigation percentage for 654 (86.7%), and within 20% of the climate adaptation percentage for 668 (88.6%).

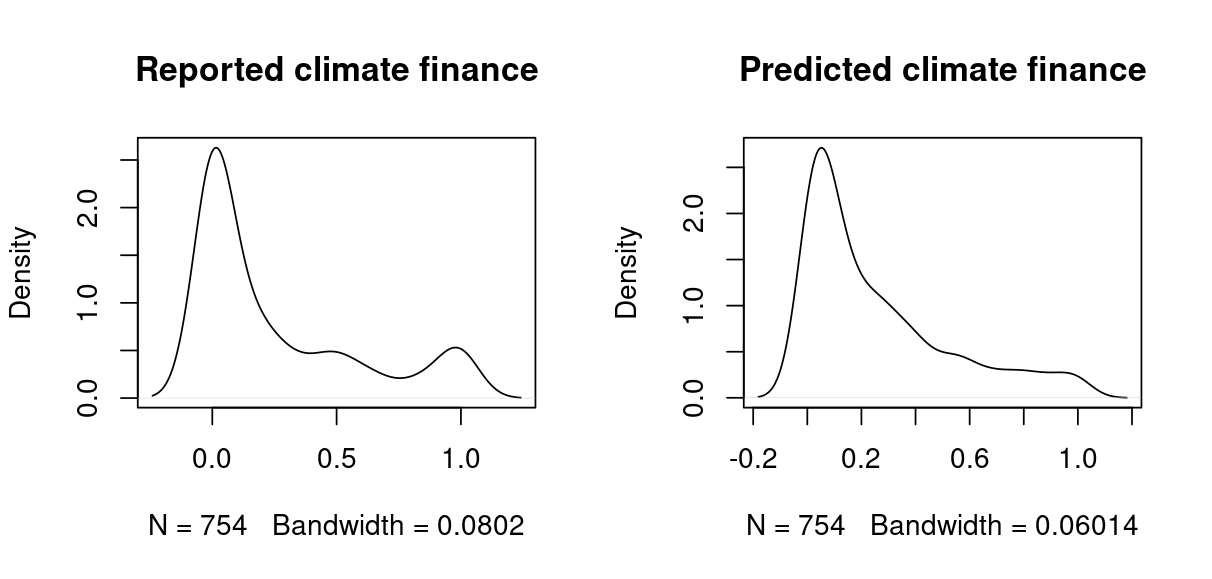

Despite the fact that the embedding vector values from BERT will generally range from -2 to 2 and be centered on zero (as logits), the MLP layer does a very good job of approximating the distribution of the training data. Predicted values graphed below are truncated from 0 to 1, but note how the model output even replicates the small heap of values at 0.5 (50%), which is likely due to the human tendency to prefer nice numbers:

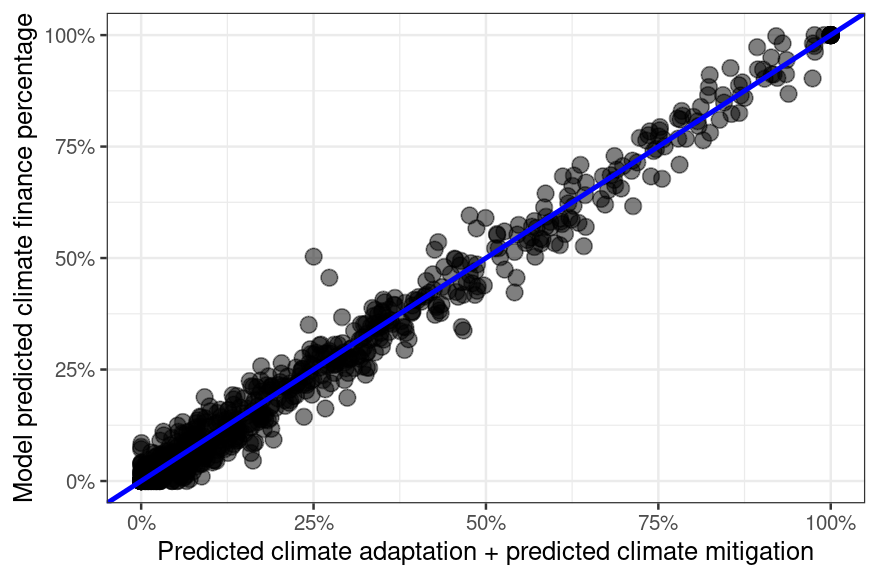

We can also test the internal consistency of the model because we are simultaneously predicting climate change, climate adaptation, and climate mitigation. The Bank typically reports climate change as the sum of both climate adaptation and mitigation. Although the model was never explicitly told that its first output should be equal to the sum of the later two, it has internalized that relationship well:

Below is a full scatterplot of the overall climate finance percentage, with the predicted values on the X axis and the reported values on the Y axis. The line in blue represents the 45 degree line, where values should be equal.

How can we use this model?

Although the predicted values do not fully match the reported values, this model goes a long way in terms of capturing the relationship between how a project is described and how much of it is actually spent on climate objectives. We can use this model as it stands to spot large discrepancies between predicted and reported values and find possible data errors. For example, the model predicts that the “Jiangxi Wuxikou Integrated Flood Management Project” should be about 80% climate finance (and 68% climate adaptation), and that prediction makes intuitive sense. The development objective states the purpose of the project is “to reduce the flood risk in the central urban area of Jingdezhen City through implementation of priority structural and non-structural measures, and contribute to establishment of an integrated flood risk management system for the City.” The Bank has labeled the above project as 42% disaster risk reduction or 43% water resource management, but has not given it a climate adaptation percentage.

On the other end of the extreme, the “Cambodia Nutrition Project II” is marked by the World Bank as 100% climate adaptation, 100% health, and 100% social inclusion, but the objectives and abstract make no reference to climate. The objective is “to improve the utilization and quality of priority maternal and child health and nutrition services for targeted groups in Cambodia.” The first component in the abstract does mention grants to “increase the sustainability of community health and nutrition activities,” but does sustainability of a health program justify counting the entire $9.5 million project as climate finance? Our model thinks no more than 10% should count.

The ability of this model to find inconsistencies in how a project is described versus how it is labeled has the potential to start a positive feedback loop of data quality. We can train an initial model on the current state of the data, find and fix inconsistent projects, and then train a new, better model on that data. Additionally, since all development and humanitarian projects in datasets like the OECD DAC CRS and IATI have accompanying qualitative descriptions, we can use our model to quantify how much of the project might have been spent on climate finance. The process of extrapolating out from World Bank project descriptions to all donors should be done slowly and carefully, however, as we cannot guarantee that other donors will describe their projects with as much information as the Bank. But as new donor texts are quantified by the model and validated by humans, we can again feed that new data into training the model so that its ability to generalize is continuously improved.